Learning from many faces and characters.

Introduction

Visual Communication evolved from dots, marks, and shapes into pictographs and letterforms and, ultimately into our familiar alphabet. This evolution parallels the development of technology from simple tools to the invention of ink/brush/woodblock stamps, paper, and the printing press.

Early stories of the religious, cultural, and political elite were written by hand using ink or pigments on paper, and scribes carved words in stone hence the phrase “carved in stone” to indicate that proclamation, rule, or contract was enacted.

The Phoenicians and their development of a written language and early alphabet connected the written language to the spoken language by creating symbols that stood for spoken sounds.

The Chinese are credited with some of the earliest known printing presses that printed Chinese works using clay characters that date back to circa 1000 A.D. In 1297 Wang Chen invented a revolving table of type using wooden type blocks.

Gutenberg Press (Moveable Type)

In 1440/1450 a German craftsman and inventor by the name of Johannes Gutenberg, working in Mainz, Germany, introduced a printing method using metal movable-type inked letters pressed onto paper. This evolution of modern printing led to the early mass production of books, making knowledge accessible to the public instead of just the rich elite and the clergy.

Metal or molten metal letterforms made the character more durable for printing exact copies from the plated original. These reversed-reading letters or characters were manually gathered and set letter-by-letter in a line and spaced mechanically using a shallow wooden tray later called a composing stick.

Mergenthaler Linotype (Hot Type)

In the late 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution was taking hold, hand-setting type was replaced by other methods that progressed finding new ways to increase the speed of how type was set. In 1884, the German immigrant and engineer, and clock/watchmaker, Ottmar Mergenthaler, concentrating on the concept of casting an entire line of type at once, invented the Linotype machine. In 1886, the Mergenthaler Printing Company was born, evolving into Mergenthaler Linotype Company. The Linotype machine was known as the eighth wonder of the world.

Using a special 90-character keyboard, this hot-metal typesetting system uses brass slugs or molds called “casting matrices” to cast entire words or sentences in a line of type (hence the name Line-o-type) in blocks of metal to a specific size and width that revolutionized typesetting – especially in newspaper publishing. The Linotype machine became one of the main methods for typesetting from the late 19th century to the 1980s when it was largely replaced by phototypesetting and later digital typesetting.

Watch type being cast on a Mergenthaler Linotype

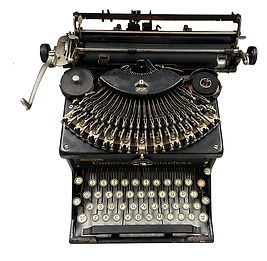

Typewriters (Strike on Typography)

The history of the typewriter was more influential than people may realize – as it was the original cold type platform. Using an inked ribbon, the first practical typewriter was patented in September, 1868 by Remington. In the following years, typewriters were built with typebars, concealing the writing. The simpler and popular Blickensderfer typewriter was introduced in 1893, using a wooden cylinder to generate the keystrikes. Pictured here is the Underwood Noiseless Typewriter (c. 1920 – 1930).

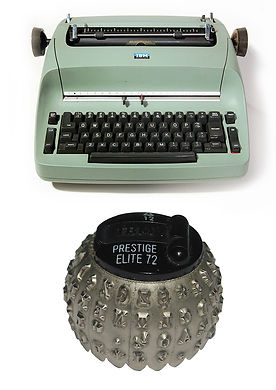

The Selectric was a highly successful line of electric typewriters introduced by IBM in 1961 that used a round “element” (called a “golf ball”) that rotated and pivoted to the correct position before striking the paper. By making the golf ball interchangeable, the Selectric enabled different fonts, including italics, scientific notation and other languages, to be used.

The Selectric also replaced the traditional typewriter’s horizontally-moving carriage with a roller that turned to advance the paper vertically. By Selectric’s 25th anniversary, in 1986, a total of more than 13 million machines had been made and sold – paving the way for the use of typewriter keyboards as the primary method for humans to interact with computers.

Phototypesetting (aka Cold Type)

In the 1960s, phototypesetting would no longer use metal blocks, and became the preferred way to set type, and the hot metal Linotype machines would become obsolete in the late 1970s to the early 1980s.

The early process used either glass (diatronic) or plastic discs – which eventually became strips of film – which contained the individual negative image of the letters of the font. The disk would spin rapidly in front of a light source, with the light exposing photo-sensitive film that printed onto photo-sensitive paper (type galleys), which would then be pasted onto art boards to be photographed again as final art to make offset-printing plates.

Typesetters could select from newly drawn type families or type families that were a redraw of earlier fonts. Typographers had greater control of size, kerning (space between letters), tracking (overall letterspacing), and leading (vertical space between lines).

As phototypesetting developed for text, the invention of the VGC PhotoTypositor by American Murray Friedel in 1959 was a major tool in the setting of display fonts for headlines. The system allowed light to pass through the negative letters on a film reel – exposing the characters on a photo paper strip below. Designers and typesetters were no longer restricted to mechanical type spacing using metal characters but were now able to control letter spacing and sizes – up to several inches.

Digital Publishing (Postscript to Variable Fonts)

The Digiset machine invented in 1968 by German engineer Rudolf Hell was the first fully digital typesetting system where the characters were reproduced using a cathode ray tube to distribute light to certain points – which are now defined as pixels.

During the 1980s Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak created the Apple MacIntosh computer – using a graphics-based operating system with a mouse and keyboard. The widespread availability made PostScript a language of choice for graphical output for printing applications using page-layout software programs, sparking the desktop publishing revolution.

PostScript allowed computers to turn vector fonts into information to send to the first laser printers on the market, while TrueType fonts (.ttf), developed at the end of the 1980s, combined all the information required to display a font on the screen and print it in a single file.

Further developments in desktop publishing fonts occurred in the mid-1990s, when Adobe and Microsoft introduced OpenType fonts (.otf), as the first digital fonts that could be used on both a Macintosh “Mac” and non-Macintosh Personal Computers “PC.”

Continuing through the mid-1990s, another revolutionary technology – the internet – had its effects on the development of typography. In 1996, a new language evolved using to define web page formatting called CSS, included font style rules for the first time. New web browsers like Netscape and Internet Explorer began supporting web fonts – formatting designed specifically for use of type on the web, with encryption codes to protect the font file and limit file sizes.

As digital services have developed over the past twenty years, online typography has become increasingly important. The same content can now be viewed on different platforms with different user experiences – on a smartphone, tablet, or desktop.

To meet the needs of all the devices, Google, Apple, Microsoft and Adobe developed Variable fonts – a single font file that behaves like multiple – fonts transitioning to various weights thicknesses, and styles. This is done by defining variations within the font, which constitute a skeleton – or multi-axis center-point. This new font format holds all of a font family’s various styles and thousands of variations with faster loading times for the web.

“THE PRACTICE OF TYPOGRAPHY” headlines on this page are inspired by a quote from Daniel Berkeley Updike (1860-1941) – an American printer and historian of type. The headline “TYPOGRAPHY” is set in 48-point American Type Founders Bulmer and the remaining text is set in English Monotype Bell. This proof was printed on a Vandercook Proof Press (SP20) at Firefly Press by John Kristensen. John is the owner of Firefly and is a frequent lecturer and instructor of printing history. He also appeared in the film LINOTYPE, released in 2012.

.png)